Definition:

A “sword” is a bladed weapon used primarily for cutting or thrusting. Typically, it consists of a long metal blade attached to a hilt with a guard.

Etymology:

The word “sword” comes from Old English “sweord,” which is of Germanic origin. It is related to Old High German “swert,” Old Norse “sverð,” and Gothic “saiws,” all meaning “sword.” The exact origin is uncertain, but the root likely refers to cutting or piercing.

Description:

Swords have varied significantly in shape and function across cultures and eras. Common types include:

- Longsword (Europe): double-edged, used for both cutting and thrusting.

- Katana (Japan): single-edged, curved, used for slicing.

- Scimitar (Middle East): curved and lightweight for slashing.

- Rapier (Renaissance Europe): thin and pointed for thrusting.

Materials also evolved, from bronze and iron to high-quality steel. Swords could be one-handed or two-handed and were often adorned, especially for ceremonial or noble purposes.

Articles:

The Word of God

Definition: The “Word of God” refers to the divine message or revelation communicated to humanity by God. This term is often used to describe sacred texts or scriptures that are…

Word

Definition: A word is a symbol that consists of a combination of letters with matching sounds, and symbolizes a meaning which can be used to construct sentences. Etymology: The word…

Symbolism:

The phrase “God’s word” is a homograph of “God sword” because both contain the exact same sequence of letters in the same order. The difference lies only in the placement of the space. While “God’s word” refers to divine scripture or communication, “God sword” evokes the image of a weapon belonging to God—often symbolizing power or judgment. These homographs highlight how the word of God function like a weapon—by wounding the believer with deception, control, and the weight of false promises. In the Bible, in Ephesians 6:17, Paul says: “the sword of the Spirit, which is the word of God.”

The Christian Cross obviously symbolizes a sword in both shape and meaning. Visually, the traditional cross—with its long vertical beam and shorter horizontal beam—resembles the form of a sword, especially when viewed upright. The sword is a weapon of war and execution; the cross, too, was originally a Roman instrument of capital punishment. The resemblance becomes even more symbolic when considering how both are associated with violence and death, and how Christianity, throughout history, has often been spread by force. From the Crusades to colonial missions, the cross was frequently carried alongside weapons such as the sword.

In the Bible, in Matthew 10:34 (NIV), Jesus says: “Do not suppose that I have come to bring peace to the earth. I did not come to bring peace, but a sword.” This statement is often interpreted as a metaphor for division and conflict—especially between those who accept His message and those who reject it. But there’s a deeper linguistic and symbolic layer worth exploring.

Jesus is often associated with the sun—the Sun of God—a celestial body that rises in the east and sets in the west. Interestingly, the word “words” is an anagram of “sword” when you move the letter S from the end (the east) to the beginning (the west). This movement mirrors the sun’s daily path across the sky—fittingly, as the letter S is often used to represent the Sun.

This rearrangement highlights a profound link: words and swords share not only letters, but also symbolism. Words have long been used as weapons—tools of persuasion, manipulation, and control. In many stories, battles arise not from brute strength but from misunderstandings and the failure to communicate. Conflict, in this sense, becomes a consequence of words gone wrong—of language twisted or weaponized.

So when Jesus says He came to bring a sword, and not peace, one could interpret that as a recognition of how His words—His teachings—would inevitably divide people. Language, after all, carries power. And like a sword, it can cut, wound, and reshape entire worlds.

Words and swords carry the same symbolism in the phrases “the pen is mightier than the sword” and “the tongue is a double-edged sword.”

Words symbolized by violence are often present in poetry, where rappers frequently use words such as “killing” and “murdering” as metaphors for being skilled with words, for being better than their opponent in rap battling, or when making insults. For example, saying “I’m killing you” means “I am better than you.”

Quote from the rap song “Eminem – Criminal”:

My words are like a dagger with a jagged edge

that’ll stab you in the head, whether you’re a fag or lez.

Manipulated language, or the inability to communicate, is often symbolically represented in storytelling through physical conflict—especially in the form of fighting. When people’s language has been shaped in a way that leads to misunderstanding or escalation, they are no longer able to resolve tension through words. Instead, they resort to violence, which reflects how corrupted communication can fuel destruction.

When it comes to sword fighting, there’s another layer of symbolism. The sword is a well-known phallic symbol, and two men fighting with swords often represents a kind of symbolic dick measuring—an expression of the fictional, toxic masculine ideal that one must prove dominance to be seen as the “alpha male.”

This act carries a homoerotic charge: two men locked in physical, rhythmic, and aggressive motion, projecting hostility that may mask repressed sexual tension. In this light, sword fighting becomes not just a symbol of power struggles, but also of internal conflict—between identity, desire, and what society demands men suppress.

In this light, sword fighting becomes symbolic of suppressed homosexual men going at each other—with physical aggression serving as a substitute for emotional or sexual expression that society has deemed unacceptable.

Although women are often shown wielding swords in art and media, the sword remains a prominent penis symbol—rooted in long-standing associations between weapons and masculinity, dominance, and sexual power. Even when women pick up the sword, the symbolism doesn’t disappear; instead, it highlights how they’re stepping into a traditionally male-coded role.

In the song “Ava Max – Kings & Queens,” she sings:

And you might think I’m weak without a sword.

But if I had one, it’d be bigger than yours.

This line plays directly on the sword-as-phallus symbolism, flipping it to assert female strength by outdoing the very symbol of male power. It’s not a rejection of the symbolism—but a bold reappropriation of it.

The swing of a sword naturally creates an arc-shaped trajectory, a motion that emphasizes the violent symbolism tied to the arc itself. The arc evokes the motion of slashing, sweeping, or cleaving—movements associated with destruction and domination. The curve of the arc visually reinforces the force and intent behind the act, making it a powerful symbol of aggression and conflict in both imagery and storytelling.

A sword, with its long, straight blade, traditionally symbolizes the penis. The crossguard — the two parts that extend horizontally between the handle and the blade — carries strong vaginal symbolism, especially when the ends are curved or bent, as is often the case in sword design. Together, the form creates a visual of a straight line entering or intersecting with a curved shape, representing the sexual act — a symbolic merging of the masculine and feminine. This makes a sword a power symbol.

However, the crossguard is not always part of a sword, meaning the sword is mainly considered just a penis symbol. Its long, straight shape naturally reflects the phallic form, and its association with strength, penetration, and domination reinforces this symbolism. Without the curved crossguard, the sword alone carries the imagery of male sexuality and assertiveness. Its use in myths, rituals, and storytelling often ties it to themes of conquest and identity, further cementing its role as a phallic symbol.

The phrase “All for one, and one for all”, famously spoken by the musketeers in Alexandre Dumas’ novel “The Three Musketeers” (1844), carries more than a message of loyalty and solidarity. Beneath its heroic tone, it acts as a symbolic expression of a structured illusion: the notion that many can become one, or that the one can become many. This mirrors the conceptual model of the trinity—not just as a religious figurehead, but as a pattern of thought and language that suggests harmony where there may be only managed fragmentation.

When the musketeers pronounce the phrase, they position themselves in a triangular, circular, or arc-shaped formation—geometric arrangements often tied to ideas of unity, eternity, and unbroken cycles. Each raises a sword, a rigid vertical object symbolizing the number 1, singularity, assertion, and masculine force. Together, they touch their swords in the center. On the surface, this represents shared purpose. Symbolically, it evokes the illusion of synthesis—an orchestrated appearance of unification.

The act of “crossing swords”—a phrase with long-standing homoerotic connotations—adds another symbolic layer. The convergence of phallic symbols in a closed circle can be read as an expression of sameness intersecting itself, hinting at both ritual union and sexual ambiguity. The gesture is theatrical, charged, and intentionally stylized.

This phrase also refers to the three dimensions of language and their illusion of coherent communication, much like the musketeers give the illusion of a perfect trinity. But language is inherently manipulated, coded, and performative. It convinces us that unity exists. The phrase thus acts as a linguistic sigil—a ritualized mantra masking fragmentation with harmony.

Yet the repeated visual of four swords—often including D’Artagnan—adds an additional, often unnoticed dimension. This fourth presence breaks the symbolic triangle and introduces a fourth point: a vertical, linear force that pierces through the cycle. It represents a fourth dimension of language. This fourth layer does not expand meaning but boxes it in, introducing control through structure. It carries significant imprisonment symbolism: the illusion of unity becomes a cage.

In essence, “All for one, and one for all” is less a bond of truth and more a mirror of constructive illusion—an encoded performance of unity that speaks to how we build, shape, and sustain what exists through symbols. With the addition of the fourth element, the ritual becomes complete: not only a call to solidarity, but a symbolic act of confinement masquerading as cohesion.

In the animated film “The Sword in the Stone” (1963), a sword tournament is taking place in town. Arthur, who is acting as a squire for a knight named Sir Kay, was supposed to bring his sword but forgets. Realizing this during the match, Arthur rushes back home to retrieve it, only to find the door locked. Desperate, he remembers the mysterious sword in the stone and decides to borrow it.

As Arthur approaches the sword, each shot shows him in profile from his right side, making only his right eye visible. This consistent framing creates a subtle symbolic focus on fantasy. Every time Arthur touches the sword, a beam of light shines down from above, adding a divine or otherworldly presence to the moment. When he finally pulls the sword free, it comes out effortlessly. Arthur then runs back to Sir Kay and presents him with the sword.

The adults around him quickly realize that this isn’t just any sword—it’s the sword from the stone. Skeptical, they demand proof. Arthur is brought back to the stone and told to pull it out again. A group of grown men try first, but none of them succeed. Then Arthur steps forward and pulls it out with ease, once again shown from his side with only his right eye visible.

The stone is surrounded by a low fence, arranged in a distinct arc shape. When Arthur draws the sword in front of the audience, the spectators also form an arc beyond the fence. The fence surrounding the sword is arranged in the shape of an arc, and the gathered audience forms a larger arc outside of it. This arc, with the sword and stone at the center, visually echoes the Star and Crescent symbol—often tied to imprisonment in fantasy. It emphasizes the impossible nature of the act, as a skinny, muscleless young boy accomplishes what an entire group of adult men could not.

Click to watch the video clips.

In the video game “The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time,” the protagonist, young Link, enters the Temple of Time and discovers a sword embedded in a stone — the legendary Master Sword. When he pulls the sword from the stone, he is transported seven years into the future, becoming an adult. The process also works in reverse: when adult Link returns the sword to its resting place, he reverts to his younger self. This mechanism allows the player to shift between two timelines, using the sword as a gateway through time.

During the moment when young Link attempts to pull the sword from the stone, the camera angle is carefully chosen. The hilt of the sword partially obscures his face, leaving only his left eye visible. This framing evokes a symbolic layer — the single visible eye hints at the illusion and fantasy of time travel, drawing attention to the mystical and illuminated nature of what’s unfolding. As the camera ascends, it reveals that Link stands on a hexagonal platform, subtly alluding to a kind of symbolic prison — a fixed structure that binds him within the rules of this fantasy world.

At the center of the platform lies the Triforce motif, iconic to the Zelda series. The Triforce, composed of three interconnected triangles forming a larger triangle, is a clear representation of the trinity — a unifying symbol of three-in-one. The Master Sword is positioned precisely at its center. This placement is rich with layered symbolism: the sword represents the number one — a defined value, a singular force — while the stone it rests in represents zero — emptiness, nonexistence, or nonvalue. Placing one within zero can be seen as a lie: an attempt to claim that “nothing” contains “something,” or that the void has inherent value. This paradox is the core of the structure of our language.

Finally, the act of drawing the sword from the stone (and returning it) is loaded with sexual symbolism. The sword is a long-standing symbol of the phallus, and the stone — a passive receptacle — echoes the image of the vagina. The entire mechanism of travel between time periods is therefore framed within a metaphor of sexual union and separation, suggesting a cyclical act of symbolic creation and return — one that mirrors the birth-death-rebirth cycle embedded in both fantasy and language itself. This sexual symbolism also serves to expose a hidden commentary: those who fail to recognize the illuminated symbolism are, in a sense, being “fucked” by it — manipulated by a system of meaning they don’t see, yet are still controlled by.

Click to watch the video clip.

In storytelling, swords are often portrayed as magical, not just as weapons but as symbols of destiny, power, transformation, and fantasy. A magical sword often arrives at the moment a hero is ready for it. It’s part of the transformation from ordinary person to legendary figure. The sword is a reward — and a test. Sometimes, the magic is illustrated visually by the sword glowing, giving it the appearance of being enchanted. It’s important to understand that “magic” is simply just another word for “fantasy.” This fantasy element is often symbolized through imagery, such as combining the form of a sword with a single eye.

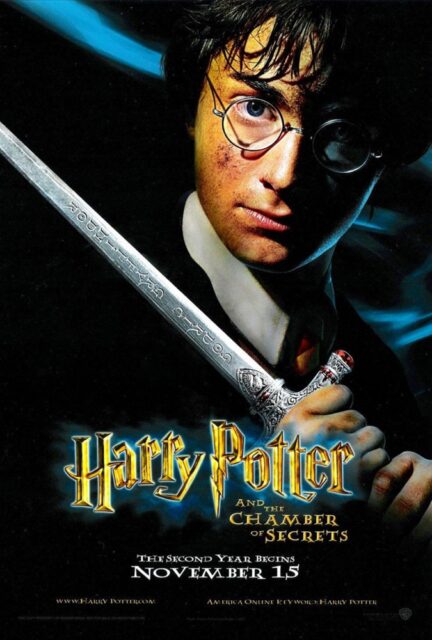

A movie poster for “Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets” (2002) features Harry Potter holding a magical sword, with his left eye hidden in the shadow, emphasizing only his right eye in the light.

Both movie posters for “The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring” (2001) and “The Return of the King” (2003) feature Aragorn holding his sword in a powerful stance, with his hair covering his left eye.

It’s very common for the Star Wars franchise to promote its movies using compositions that combine their iconic laser swords with one–eye symbolism, emphasizing the fantasy nature of the weapons and the mythic, otherworldly tone of the entire Star Wars universe.

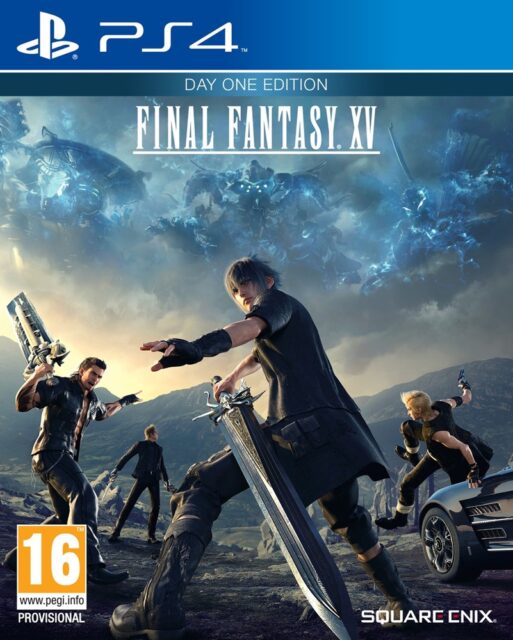

The “Final Fantasy” game series often features one–eye symbolism on its cover art, reflecting the eye as a symbol of fantasy. On the cover of “Final Fantasy XV,” several characters are shown posing with swords, blending this symbolic element with the series’ signature blend of magic and combat.

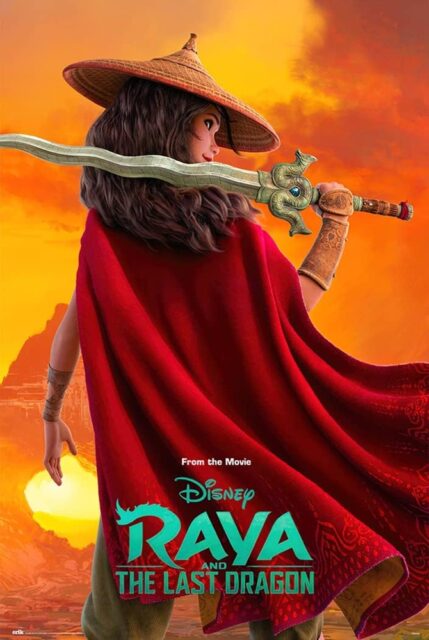

The poster for the animated movie “Raya and the Last Dragon” (2021) shows Raya viewed from behind, wearing a wide-brimmed hat and a flowing red cape. She rests a curved sword across the back of her neck, with one hand gripping the hilt. Raya turns her head to the right, looking over her shoulder, making only her right eye visible to the viewer. The wide-brimmed hat, the curved sword, and the arched shape of the red cape all carry arc symbolism. Together with the one–eye framing, this combination of visual elements closely resembles the Star and Crescent symbol.

The poster for the movie “Sword of God” (2018) features the main character standing in dark armor with a large sword sheathed at his waist. He looks down solemnly while a crowd of outstretched hands rises up toward him from below, suggesting desperation or a plea for help. In the bottom right corner, one of the figures is seen from the left side, with only the left eye visible—positioned closely beside the sword. The imagery reinforces a symbolic connection between God and the sword, while the one–eye symbolism highlight the fantasy aspect of God and His sword.

The movie poster for “Sword of Vengeance” (2015) features a dramatic close-up of a warrior with a blood-smeared face, looking downward at his sword, which is streaked with fresh blood. He grips the weapon tightly, and only his left eye is visible beneath his furrowed brow. The intense focus on the blade and the solitary eye emphasizes the fantasy-driven theme of vengeance, while also highlighting the sword as a fantasy symbol.

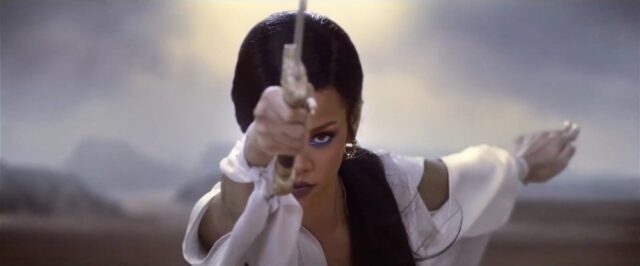

In the music video “Coldplay – Princess of China (ft. Rihanna),” Rihanna performs a sword movement that begins vertically and sweeps downward in an arc trajectory. As the sword passes across her face, it temporarily covers her right eye, leaving only her left eye visible. This moment combines one–eye framing with the curved motion of the sword, creating what resembles the Star and Crescent symbol.

The fictional character King Arthur, famous for pulling the sword from the stone, appears on the movie poster for “King Arthur: Legend of the Sword” (2017) with the right side of his face covered by a red overlay, leaving only his left eye visible.

Two posters for “Excalibur” (1981) both feature the legendary sword associated with King Arthur, each using distinct one–eye symbolism. In the first poster, the sword stands vertically in the center, dividing the image into two halves, with each side showing what appears to maybe be a different face—suggesting a duality, contrast, or split personality. In the second poster, the sword is again central, but behind it is a demonic-looking figure whose eyes are mismatched, with one eye appearing more pronounced or glowing.

The movie poster for “Kirpaan: The Sword of Honour” (2014) features a prominently placed curved sword running vertically through the center of the image. On each side of the blade is half of a different man’s face, with only one eye visible from each. The combination of the curved sword and the one–eye framing visually resembles the Star and Crescent symbol, creating a striking and symbolic composition.

The movie poster for “The Sword” (2021) features a vertical sword in the center, dividing the image into two contrasting halves. On the left side is the face of a blue-toned, monstrous figure, while the right side shows a man with a red overlay across his left eye. Only one eye is visible for each character. The poster uses strong red vs. blue symbolism, emphasizing a clear opposition between the two characters.

The movie poster for “Warcraft: The Beginning” (2016) features a large vertical sword in the center, dividing the image into two opposing sides. On the left is a red-toned orc with large tusks and war paint, while on the right is a human warrior with blue paint covering half his face. Only one eye of each character is visible, highlighting the fantasy aspect of this fictional universe. Below them, both sides show their respective factions—one red and tribal, the other blue and armored—emphasizing a red vs. blue visual contrast that highlights the conflict between the two worlds.

“Mulan” tells the story of a young woman who disguises herself as a man to take her father’s place in the army. Both the 1998 animated film and the 2020 live-action adaptation use a similar visual motif in their posters to represent this transformation. In each poster, Mulan holds a sword vertically in front of her face, covering her left eye. Reflected in the blade is her male warrior identity, visually splitting her face into two roles—one as a woman, and the other as a male soldier. This composition highlights her internal conflict and the fictional struggle with gender identity that lies at the heart of the story.

When a sword is pointed upwards, it often carries symbolic weight beyond simple combat readiness. In many visual and symbolic traditions, the upward-pointing sword can echo the meaning of the inverted cross—also known as the Cross of St. Peter. Though originally a Christian symbol of humility, the upside-down cross has, in modern times, become associated with rebellion and Satanism due to its reversal of the traditional Christian Cross.

Similarly, raising a sword toward the sky can be interpreted as a symbolic challenge or defiance toward a higher power. The sky, often representing heaven or divinity, becomes the target of the weapon. In this context, the upward thrust of the blade can represent not only aggression but a symbolic act of “attacking God” or rejecting divine authority. This visual can be found in various artworks, literature, and occult imagery where the sword becomes more than a weapon—it becomes a statement of revolt against spiritual order.

The video game “The Legend of Zelda: Skyward Sword” weaves the symbolic act of raising a sword toward the sky into its title, gameplay, and visual presentation. The very name “Skyward Sword” emphasizes this gesture—lifting the blade heavenward—as a central theme. It’s not just a gameplay mechanic; it’s a motif of seeking power from above.

Throughout the game, Link frequently raises his sword skyward to charge it with energy described as coming from the heavens. This motion empowers the blade, imbuing it with light and granting it abilities it wouldn’t have otherwise—suggesting that divine energy or celestial power flows into the weapon when it is pointed toward the sky. This action becomes essential to progress in the game, reinforcing its symbolic importance.

Even the cover art highlights this motif, depicting Link holding his sword high above his head, emphasizing the upward gesture as iconic and meaningful. In this way, “Skyward Sword” builds its entire identity around this repeated visual and thematic idea: that power, guidance, and transformation come through the upward connection between the sword—and the one who wields it—and the heavens.

The movie poster for “Conan the Barbarian” (1982) prominently features Conan standing powerfully with his left arm raised, holding a sword pointed toward the sky. This upward gesture not only emphasizes strength and defiance but also mirrors a long-standing visual motif where a raised sword becomes more than a weapon—it becomes a symbol. The pose suggests dominance, power drawn from above, and an almost divine or mythic connection.

The logo at the top of the poster reinforces the sword’s importance. The horizontal sword in the title slashes through the word “Conan,” piercing each letter and visually asserting itself as the central element. This creates a clear phallic association, with the sword doubling as a symbol of masculine virility and aggressive sexuality. Its placement and orientation—directly through the name—deliberately evoke forceful and penetrative imagery, blending violence and sexual symbolism in a way that reflects the raw tone of the film.

Notably, the sword Conan holds aloft intersects visually with the logo’s horizontal sword, forming a cross-like composition. This crossing of blades, especially when framed so centrally on Conan’s body, can be interpreted as an intentional layering of sexual undertones—where the vertical and horizontal swords converge not just as weapons, but as symbols of homosexual desire. This interplay hints at the homoerotic dimension often discussed in interpretations of the Conan character: a hypermasculine figure whose exaggerated physicality, lack of emotional vulnerability, and frequent display of bare flesh speaks to both dominance and eroticism. The visual crossing of the two swords thus becomes an emblem of dual symbolic weight—celebrating masculinity while also opening space for alternative readings of Conan’s character through a queer lens.

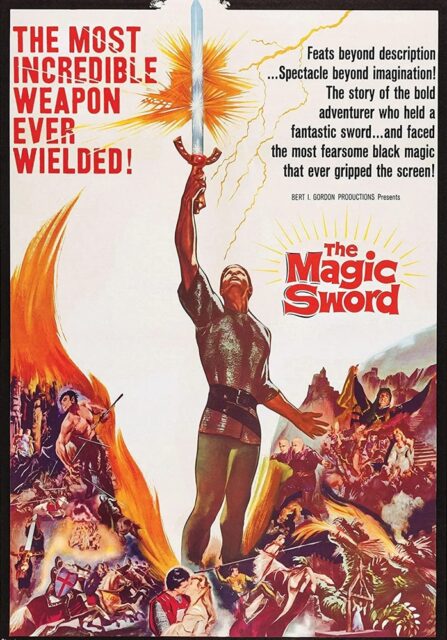

The poster for “The Magic Sword” (1962) prominently features a heroic figure standing tall at the center, raising a glowing sword high into the sky with his right hand. The blade appears to be struck by golden lightning, radiating light and energy, which emphasizes the sword’s magical and supernatural qualities. This visual not only dramatizes the moment but also establishes the sword as a conduit of power, possibly divine or enchanted.

The title, “The Magic Sword,” reinforces this idea by explicitly framing the weapon as a fantastical object. Unlike a typical sword, this one is elevated into the realm of myth and legend. The bold, red typography and radiant lines behind the title further amplify the fantasy theme, making it clear that the sword is not just a tool for battle, but the centerpiece of the story’s magical adventure. The poster captures the sword as both a literal weapon and a symbol of heroic transformation and wonder.

A sword of some form is featured on the national flags of Angola, Bangsamoro, Oman, Saudi Arabia, and Sri Lanka.

Articles:

Greek Cross

Definition: The “Greek Cross” is a type of cross with four arms of equal length, intersecting at right angles. Etymology: The term “Greek Cross” originates from its prominent use in…

Jerusalem Cross

Definition: The “Jerusalem Cross,” also known as the “Crusader’s Cross,” is a Christian symbol consisting of a large cross potent (a cross with crossbars at the ends) surrounded by four…

Maypole

Definition: A “maypole” is a tall wooden pole, often decorated with ribbons, flowers, and other ornaments, or made to resemble the Christian cross, that serves as the focal point for…

Orthodox Cross

Definition: The “Orthodox Cross,” often referred to as the Russian Orthodox Cross, is a distinct Christian cross associated particularly with the Eastern Orthodox Church. Etymology: The term “Orthodox” comes from…

Patriarchal Cross

Definition: The “Patriarchal Cross” is a variant of the Christian Cross featuring two horizontal crossbars, with the upper one shorter than the lower one. Etymology: The term “patriarchal” comes from…

Pattée Cross

Definition: The “Pattée Cross” (also spelled “Pattee”, “Patee”, or “Paty”) is a distinct form of Christian cross with arms that are narrow at the center and flare out in a…

Southern Cross

Definition: The “Southern Cross” refers to a prominent constellation officially known as “Crux.” It is visible in the southern hemisphere and is composed of five stars that form a cross-like…

Tau Cross

Definition: The “Tau Cross” is a T-shaped cross, resembling the Greek letter tau (Τ or τ). Etymology: The term “Tau” derives from the Greek letter “ταῦ” (tau), which was used…

Trefoil Cross

Definition: The Trefoil Cross is a symbol that combines the traditional Latin Cross shape with three rounded lobes at the end of each arm, creating a design that resembles a…

White Nationalist Celtic Cross

Definition: The term “White Nationalist Celtic Cross” refers to a specific adaptation of the traditional Celtic cross that has been appropriated by white nationalist and white supremacist groups. Etymology: The…

Religion:

Swords are frequently mentioned in the Bible, symbolizing divine judgment, protection, and conflict between good and evil.

In the Bible, in Ephesians chapter 6, verse 17, it says: “Take the helmet of salvation and the sword of the Spirit, which is the word of God.”

In the Bible, in Genesis chapter 3, verse 24, it says: “So he drove out the man; and he placed at the east of the garden of Eden Cherubims, and a flaming sword which turned every way, to keep the way of the tree of life.”

In the Bible, in Matthew chapter 10, verse 34, it says: “Think not that I am come to send peace on earth: I came not to send peace, but a sword.”

Swords are mentioned in the Quran, both literally and symbolically, particularly in the context of battle and justice.

In the Quran, in Surah Muhammad, verse 4, it says: “So when you meet those who disbelieve [in battle], strike [their] necks until, when you have inflicted slaughter upon them, then secure their bonds…”

In the Book of Mormon, in Alma chapter 24, verse 12, it says: “And now behold, my brethren, since it has been all that we could do…to repent of all our sins and the many murders which we have committed, and to get God to take them away from our hearts—for it was all we could do to repent sufficiently before God that he would take away our stain—” (referring to the burying of swords as a symbol of peace).

Swords are central in Norse mythology, often bearing names and magical properties. Odin’s sword “Gram” and Sigurd’s reforged sword “Gram” (also called “Balmung”) play key roles in the heroic sagas.