Definition:

“To know” is to be 100% certain that something is accurate by having proof.

Etymology:

The word “knowledge” derives from Middle English “knouleche,” from the verb “knowlechen,” which means “to acknowledge” or “to recognize.” This in turn came from “knowen” (to know) + “-leche,” a suffix related to the action or condition of a verb. Ultimately, “know” is rooted in the Old English “cnāwan,” meaning “to know,” which is related to the Proto-Germanic “knew-” and the Proto-Indo-European root “ǵnō-” meaning “to know.”

Description:

Being 100% sure that something is accurate means that you can test something repeatedly, and that you get the same result 100% of the times you test it. As soon as it happens at least once that you do not get the same result, you cannot be 100% sure that it is accurate anymore. It can often happen that one believe they’re 100% sure that something is accurate, but then a case will appear where the test produces a different result. This means that one never knew, but that one believed.

The word “science” comes from the Latin “scientia,” meaning “knowledge,” which in turn derives from “sciō,” meaning “I know.” This etymology has led many to assume that if something is scientific, it means “we know” it to be true. However, the problem lies in how knowledge is defined within scientific discourse. In science, knowledge does not imply certainty or absolute truth. It can include ideas that are provisional, subject to revision, or even ultimately false.

One of the most widely accepted principles in science—almost a golden rule—is the idea that “we can never be 100% certain about anything.” Yet this statement contains a built-in paradox: it expresses 100% certainty about the impossibility of certainty. A more logically consistent version would be, “We don’t know whether 100% certainty is possible.”

And yet, some truths are undeniably certain. For example, the fact that existence exists is self-evident and logically necessary. To deny it is to affirm it. Still, such foundational certainties are often ignored or sidelined in scientific language, revealing a deeper inconsistency in how science defines and applies the concept of knowledge.

What science actually does, in practice, is define “knowledge” in much the same way we define “belief.” The key difference is that, within scientific language, knowledge is treated as a more accurate, evidence-based, and reliable form of belief. In other words, it’s still belief—but belief backed by observation, testing, and rational consistency.

In contrast, religious language takes almost the opposite approach. In that framework, both “belief” and “knowledge” can imply 100% certainty. Like science, religion does tend to rank knowledge as more credible than belief. But the twist lies in how it claims we arrive at knowledge: not through observation or evidence, but by “believing.” In religious language, believing is the path to knowing.

The real linguistic sleight of hand comes with the idea of “faith.” Faith is presented as something that transcends both knowledge and belief. Yet, in practice, faith simply means believing despite proof to the contrary. Religious language often begins with the assumption that God exists, treating this as a logical starting point. From there, any reasoning that maintains this assumption is classified as knowledge—regardless of whether it’s logically sound. This form of “knowledge” is not acquired through questioning or testing, but by believing. And even when the reasoning is demonstrably flawed, “faith” is what keeps the illusion of certainty intact.

Both scientific language and religious language are, in many ways, dishonest. They often pressure people into choosing a side—into believing something, rather than acknowledging uncertainty.

Religions typically demand belief in the existence of God, in sacred texts, in religious authorities, and in whatever supports those beliefs—whether that means the Earth is flat, only a few thousand years old, that dinosaurs never existed, or that humanity originated from Adam and Eve.

Likewise, the scientific community often insists that you accept its theories as true. If you lack access to the data, or simply don’t understand the complex explanations, you’re still expected to believe the scientific consensus: that the Earth is round, billions of years old, that dinosaurs existed, and that life evolved through natural processes.

What’s rarely encouraged—by either side—is admitting that you simply don’t know. Yet this is arguably the most honest position. Unfortunately, admitting uncertainty is often met with ridicule or dismissal. Both religious believers and scientific advocates frequently attack this position by misrepresenting it—building straw man arguments to avoid addressing the challenge it presents.

Why? Because it’s hard to argue against uncertainty when you don’t actually have proof—only belief or consensus. For example, round-Earth proponents often argue that the Earth must be round because flat-Earth claims are wrong—without providing direct, understandable proof for their own view. Flat-Earth proponents do the same in reverse: attacking flaws in mainstream science instead of offering solid proof for a flat Earth.

In both cases, the debate becomes less about truth and more about defending a side. And the simple act of saying “I don’t know” becomes a radical act of intellectual honesty.

The prevailing belief that nothing can be known with 100% certainty has inadvertently cultivated a kind of irrational fear—one that makes people highly susceptible to confirmation bias. In the pursuit of the dopamine rush that comes from the illusion of gaining knowledge, many become overly eager to accept anything that appears to affirm their existing views, regardless of its actual truth. Ironically, those who most adamantly proclaim “we can’t know anything for certain” are often the same individuals who insist that certain claims—especially those from authority figures—”must be true.” Their logic follows: “if we can’t believe anything with certainty, then we must cling to what experts say, otherwise progress becomes impossible.”

This mindset has become so normalized that the simple act of admitting uncertainty is now rare. As a result, most people are unaware that there are, in fact, many things we can know with absolute certainty. And when someone chooses to focus solely on what is undeniably certain—rejecting belief in anything uncertain—they often undergo a profound transformation. Within just a few hours of clear, critical reflection, such a person can become vastly more knowledgeable than the average individual. This is not because they acquire more information, but because their thinking becomes purified from illusion, anchored in certainty, and free from the constant sway of ungrounded belief.

Articles:

Belief

Definition: “Belief” is to accept something as accurate without proof. “Faith” is to accept something as accurate even when you have proof to the contrary. Etymology: The word “believe” originates…

Love

Definition: The word “love” is a label for a complex and multifaceted emotion, encompassing feelings of deep affection, attachment, care, and compassion for someone, something or some idea. It comes…

Proof vs. Evidence

Definition: “Proof” is a demonstration that establishes a statement as 100% accurate. “Evidence” is information or data that supports the accuracy or validity of a claim, but does not imply…

Science

Definition: “Science” is a structured and methodical approach to acquiring knowledge, using observation, experimentation, and reasoning to understand, explain, and predict phenomena—whether in the natural world (as in physics or…

Symbolism:

Even though “ǵnō-” (to know) and “kʷeid-” (to shine, be bright) are distinct Proto-Indo-European (PIE) roots, many ancient languages and cultures symbolically associated knowledge with light or whiteness. This suggests a conceptual connection, even if not a direct etymological one. In esoteric language, light is a metaphor for understanding, while darkness represents ignorance — a theme seen across religious texts, philosophy, and mythology. However, darkness is actually the illuminated symbol of absolute certainty, while light represents ignorance.

The word “knowledge” is the basis for the word “science“, from the Latin “scientia” (“to know”). This relationship is especially clear in Germanic languages. For example, in Norwegian, “vitenskap” means “science” or more literally “the creation or body of knowledge,” which contains the prefix “vit-.” The verb “å vite” means “to know” and shares roots with other Germanic words like “wissen” (German) and “wit” (archaic English).

Interestingly, “å vite” is a homophone of “å hvite”, a rare or poetic verb form meaning “to whiten.” The word “hvit” means “white” in Norwegian. Although these words have different etymological origins (“vite” from PIE “ǵnō-,” and “hvit” from PIE “kʷeid-“), their phonetic similarity in Norwegian reflects the deeper symbolic connection between knowing and light or whiteness — where to “know” is metaphorically to “make clear.”

Articles:

Christmas Tree

Definition: A “Christmas tree” is an evergreen tree, often a fir, spruce, or pine, decorated with lights, ornaments, tinsel, and other Christmas decorations. Etymology: The term “Christmas tree” combines “Christmas,”…

Cone

Definition: A “cone” is a geometric figure with a circular base that tapers evenly to a single point, called the apex. Etymology: The word “cone” originates from the Latin word…

Conical Shell

Definition: A “conical shell” refers to a type of seashell that has a conical shape. Etymology: The term “conical” comes from the Greek “konikos,” meaning cone-shaped. “Shell” derives from the…

Conical Topiary Tree

Definition: A “conical topiary tree” is a tree or shrub that has been pruned and shaped into a cone form. Etymology: The term “topiary” comes from the Latin “topiarius,” meaning…

Cosmic Mountain

Definition: A “cosmic mountain” is a symbolic and mythological representation of a sacred or significant mountain that connects the heavens and the earth. It is seen as a central axis…

Illuminati

Definition: “Illuminati” refers to individuals who understand how language, religion, and the world system are scams. Etymology: The term “Illuminati” originates from Latin and means “the enlightened.” It is derived…

Love

Definition: The word “love” is a label for a complex and multifaceted emotion, encompassing feelings of deep affection, attachment, care, and compassion for someone, something or some idea. It comes…

Mountain

Definition: A “mountain” is a large natural elevation of the earth’s surface that rises steeply from the surrounding level. Mountains are formed through geological processes such as plate tectonics, volcanic…

The Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil

Peter Paul Rubens – The Fall of Man (1628-1629). Charles Joseph Natoire – The Rebuke of Adam and Eve (1740). Definition: “The Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil,”…

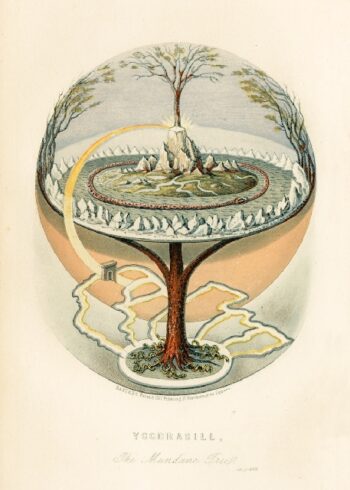

The World Tree

Oluf Olufsen Bagge – Yggdrasil, The Mundane Tree (1847). “The World Tree” is illustrated as a massive tree holding up the world with its three branches. The world is inside…

Tornado

Definition: A “tornado” is a rapidly rotating column of air that extends from a thunderstorm to the ground. It is characterized by its funnel shape and intense winds, which can…

Tower of Babel

Pieter Bruegel the Elder: The Tower of Babel (1563). Lucas van Valckenborch: Tower of Babel (1594). Gustave Doré: The Confusion of Tongues. Definition: The “Tower of Babel,” also known as…

Traffic Cone

Definition: A “traffic cone” is a brightly colored, conical-shaped safety device used to delineate traffic lanes or to redirect vehicles and pedestrians in a controlled manner. Etymology: The term “traffic…

Triangle

Definition: A “triangle” is a geometric figure consisting of three lines that meet at three corners, also called angles or vertices. The sum of the three angles in a triangle…

Volcano

Definition: A “volcano” is a geological formation, typically a mountain, where molten rock (magma), ash, and gases from the Earth’s interior erupt through the Earth’s crust. Etymology: The word “volcano”…

Witch’s Hat

Definition: A “witch’s hat” is a hat worn by a witch. It’s typically a tall pointed, cone-shaped black hat with a wide brim. Etymology: The term “witch” comes from the…

Wizard’s Hat

Definition: A “wizard’s hat” is a hat worn by a wizard. It’s typically a tall pointed, cone-shaped hat with a wide brim, adorned with stars, moons, or other mystical symbols….

Religion:

When it comes to knowledge, religious texts across the world generally agree on one thing: it’s important. But how they talk about knowledge—and what kind they value most—can vary quite a bit.

In the Abrahamic traditions—Judaism, Christianity, and Islam—knowledge is often seen as something that begins with God. For example, the Hebrew Bible (Tanakh) says in Proverbs 1:7, “The fear of the Lord is the beginning of knowledge.” The idea here is that God is the only absolute certainty there is. Questioning God is off-limits. So, fear of God is what defines the starting point of knowledge in these traditions. You don’t begin by asking questions—you begin by submitting to divine authority. From that foundation, knowledge is allowed to grow, but always within the boundaries of belief.

Christian texts follow a similar logic. In the Bible, in James, chapter 1, verse 5, it says, “If any of you lacks wisdom, let him ask of God…”—again pointing to God as the only true source of wisdom. At the same time, 1 Corinthians 8:1 offers a warning: “Knowledge puffs up, but love builds up.” In other words, intellectual pride is dangerous unless it’s grounded in faith and love. Knowledge that drifts too far from obedience becomes a threat. However, the illuminated meaning of love is actually ignorance, which complements this Bible quote quite well.

In Islam, knowledge is not just valued—it’s required. The very first word revealed in the Qur’an was “Iqra” (Read!) in Surah Al-‘Alaq 96:1, which sets the tone for a religion that reveres learning. But again, there are boundaries. The Qur’an emphasizes that true knowledge comes from God, and understanding must align with revelation. In Surah Al-Mujadila, 58:11 says, “Allah will raise those who believe and those who have been given knowledge in degrees.” And in Hadith (Sunan Ibn Majah, Book 1, Hadith 224), the Prophet Muhammad says, “Seeking knowledge is an obligation upon every Muslim.” But it’s not just any knowledge—it’s knowledge that affirms faith and strengthens submission to God’s will.

Eastern traditions often place more emphasis on self-knowledge and inner realization. In Hinduism, knowledge—jnana—is one of several valid paths to spiritual freedom. The Bhagavad Gita 4:38 says, “There is no purifier equal to knowledge…” But this is not about facts or scriptures—it’s about realizing the truth of who you are. The Upanishads, such as the Chandogya Upanishad 6.8.7, teach that knowing the self is the same as knowing ultimate reality: “He who knows the Self, knows all.” Hinduism is promoting all kinds of fantasies. In this context, the religion is focusing on promoting the illusion of identity as truth.

The Tao Te Ching, in Chapter 33, says, “He who knows others is clever; he who knows himself is wise.” It doesn’t elevate any divine being as the source of truth. Instead, it encourages intuitive understanding and harmony with the natural flow of life (the Tao). Too much thinking or intellectualizing is seen as a barrier.