Definition:

he “Christian Cross,” also known as the “Latin Cross,” is a symbol of Christianity, representing the crucifixion of Jesus Christ and His resurrection.

Etymology:

The word “cross” comes from the Latin “crux,” which originally referred to a tree or wooden structure used for executions. The Old English word “cros” was borrowed from Old Norse “kross,” which was itself derived from Latin.

Description:

The Christian Cross is one of the most recognized religious symbols in the world and is used in various forms across different Christian denominations.

The Christian Cross originates from one of the most brutal execution methods used in the ancient world—crucifixion. Far from being a mere religious emblem, the cross was an instrument of torture and death, designed to prolong suffering and publicly humiliate the condemned.

In Catholicism, the Christian Cross is most often the crucifix, featuring the figure of Jesus, meant to symbolize Christ’s suffering. Protestantism, on the other hand, tends to favor the empty cross, representing the resurrection and victory over death. But regardless of interpretation, the fact remains that the central symbol of Christianity— a religion that claims to focus on peace and love—is a device of torture and execution. Christians have seen it so often that many have become numb to its brutal origins, treating it as a comforting or even sacred image rather than what it actually is. This has led to a growing trend of anti-theists pointing out that if Jesus had been executed by guillotine, Christians would likely be wearing guillotine necklaces instead, which only points out the absurdity of glorifying a method of torture. Some also question how Jesus Himself would feel about people worshipping the very device He was tortured on, raising the irony of a movement built around His suffering, yet embracing the symbol of His agony as a sign of devotion.

“INRI” stands for “Iesus Nazarenus, Rex Iudaeorum,” meaning “Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews.” This inscription was placed on the cross by order of Pontius Pilate, written in Hebrew, Latin, and Greek (John 19:19-20). While it originally served as a formal charge, Christians later saw it as a declaration of Jesus’ true identity. Interestingly, the letter R in “INRI” can be seen as an equality symbol, making “INRI” visually represent “IN = I”—suggesting that “I” and “In” carry the same meaning. This interpretation highlights the idea that Jesus, as an individual (“I”), is inseparable from his role as “Jesus of Nazareth” (“In”), reinforcing the connection between his personal identity and his mission.

Articles:

Christmas

Definition: “Christmas celebration” is an annual Christian holiday that commemorates the birth of the fictional character Jesus Christ (Nativity of Jesus). Christmas itself is one day (Christmas Day), but the…

Christmas Church Service

Definition: A “Christmas church service” is a religious ceremony held in Christian churches to celebrate the birth of Jesus Christ. These services can take place on Christmas Eve, Christmas Day,…

Easter

Definition: “Easter celebration” is an annual Christian holiday that commemorates the resurrection of the fictional character Jesus Christ from the dead. Easter itself is one day (Easter Sunday), but the…

Easter Church Service

Definition: An “Easter church service” is a religious ceremony held in Christian churches to celebrate the resurrection of Jesus Christ from the dead. It is considered the most important and…

Passion of Christ

Definition: The “Passion of Christ” is a fictional story that refers to the final period of Jesus Christ’s life, encompassing his suffering, crucifixion, and death. This period is central to…

Symbolism:

Jesus is a metaphor for the Sun, and His story reflects the Sun’s movement through the sky. Christmas aligns with the winter solstice, marking the Sun’s lowest point before it begins to rise again, while Easter is tied to the spring equinox, when daylight overtakes darkness. The crucifixion and resurrection of Jesus represent this shift, with His death symbolizing the Sun’s descent and His return marking its rise.

The image of Jesus on the Cross reflects an astronomical event where the Sun appears to descend onto the constellation known as the Southern Cross before shifting upward again. Just as the Sun reaches this point before beginning its ascent, Jesus is said to die on the Cross before rising again. The Southern Cross serves as a celestial marker for this transition, mirroring the story’s structure.

Older solar myths followed the same pattern, linking the Sun’s movement to cycles of death and rebirth. The Egyptian god Osiris was associated with the Sun setting into the underworld before rising again, symbolizing renewal. The Persian god Mithras was linked to the winter solstice as a point of rebirth, similar to Jesus’ resurrection. The story of the dying-and-rising god can also be seen in the myths of Attis and Tammuz, who, like Jesus, were figures connected to seasonal changes and the return of light. These stories were present long before Christianity and followed the same structure of the Sun’s disappearance and re-emergence.

From a specific location on Earth, there must be times when the Sun appears to align with the Southern Cross. The key is that the apparent position of the Sun changes throughout the year due to Earth’s orbit, and different constellations become visible at different times of the night or year. Since the Southern Cross (Crux) is located in the far southern sky, it is visible mainly from the Southern Hemisphere. If someone were positioned far enough south, there would likely be a time when the Sun appears to “pass over” or be near the Southern Cross during the day. However, because the brightness of the Sun completely outshines the stars, this event wouldn’t be visible to the naked eye. But it demonstrates early understanding of astronomy. To determine exactly when and where this happens, one would need to track the Sun’s position relative to the Southern Cross using astronomical software or star charts. It’s not something commonly photographed because the sky around the Sun is too bright for the constellation to be visible, but theoretically, the Sun should cross or come close to the Southern Cross from certain latitudes at specific times of the year.

The modern Christian Cross, most commonly represented as the Latin Cross (✝), typically consists of two intersecting lines or beams, forming a T-shape with a longer vertical beam.

The letter “T” is closely linked to the Christian Cross because of its shape, which resembles a crucifix. Historically, the Tau Cross (†), named after the Greek letter Tau (Τ, τ), was a common form of crucifixion device in ancient times. Early Christians, particularly St. Francis of Assisi and his followers, used the Tau Cross as a sacred symbol, seeing it as a representation of Christ’s sacrifice. Over time, the Latin Cross (✝) became the dominant Christian symbol, but the T remains a visual reminder of the cross, connecting language and religion.

Similarly, the letter “Y” has been associated with Jesus Christ, as its shape can be seen as representing the figure of a person with arms raised in prayer or surrender. When the letters Y and T are combined—such as in YT or TY—they create a visual and conceptual representation of Jesus on the Cross, with Y symbolizing His raised arms and T forming the structure of the crucifixion. This pairing deepens the connection between language and religion, reinforcing how letters and symbols carry profound theological meaning.

The Greek Cross (✚) is a cross with four arms of equal length, creating a perfectly balanced shape. Unlike the Latin Cross, which has a longer vertical arm, the Greek Cross is symmetrical in all directions. This shape has been widely used throughout history, appearing in ancient art, architecture, and religious symbolism. It was a common design in Byzantine churches, seen in mosaics, floor plans, and iconography. The cross’s balanced form gave it a sense of harmony and stability, which may be why it was later adopted as the plus symbol in mathematics. The connection between the two isn’t just a coincidence—symbols are often chosen for their meaning, and the Greek Cross already carried an association with order and structure.

The Crucifix is a symbol of Jesus crucified on the Christian Cross, emphasizing His suffering and sacrifice. While all Christians recognize the significance of the cross, the Crucifix is more commonly used by Catholics, who place a much greater focus on Jesus’ suffering as a central part of their faith. This emphasis is reflected in their art, prayers, and traditions, where the Crucifix serves as a constant reminder of His sacrifice for humanity.

The Celtic Cross combines a traditional Latin Cross with a circle at its center, and that circle represents the Sun. Jesus is a metaphor for the Sun, and the design of the cross reflects an astronomical event where the Sun lowers onto the constellation known as the Southern Cross before shifting upward again. This pattern connects Jesus’ story to the Sun’s movement, similar to older solar myths that existed long before Christianity.

The four open spaces created where the circle and the cross intersect symbolize the four seasons of the year, linking the cross to the natural cycle of the Sun. The circle is also the symbol of zero, which is synonymous with nonexistence. In this sense, the circle on the Celtic Cross represents Jesus’ nonexistence, emphasizing that the story of Jesus is fictional. In the context of zero, the four hollow sections between the circle and the cross symbolize the imprisonment that comes from believing in the story, reinforcing the idea that it is an illusion. The Celtic Cross visually captures both the movement of the Sun and the structure of a belief system built around a myth.

The Patriarchal Cross is a variant of the Latin Cross featuring two horizontal crossbars, with the upper one shorter than the lower one. It is commonly associated with Eastern Orthodox, Byzantine Catholic, and some Eastern European Christian traditions. The upper bar represents the inscription placed above Jesus’ head on the cross—often abbreviated as “INRI”—while the longer lower bar represents where Christ’s arms were nailed.

The Patriarchal Cross is often linked to ecclesiastical authority and heraldry, particularly in Hungary, Slovakia, and Lithuania.

The Orthodox Cross, often referred to as the Russian Orthodox Cross, is distinct from the more commonly recognized Latin Cross because it has three horizontal beams instead of just one. The top beam is small and represents the inscription that was placed above Jesus’ head during the crucifixion, often written as “INRI,” which stands for “Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews.” The middle beam is the longest and is where Christ’s hands were nailed. The lowest beam is slanted, representing the footrest, or “suppedaneum.”

The slanting footrest is often said to reflect the two thieves who were crucified alongside Jesus. According to Christian tradition, the repentant thief, Dismas, was on Jesus’ right, and the unrepentant thief, Gestas, was on Jesus’ left. Jesus promised Dismas that he would be with Him in paradise, while Gestas mocked Him and was condemned. Some interpretations claim that the slanted beam symbolizes their fates—the upward tilt representing the saved thief, and the downward tilt representing the damned thief. However, this presents an apparent symbolic inconsistency, as in most religious traditions, the right is associated with heaven and the left with judgment or damnation.

Some scholars suggest that this inconsistency is resolved if the cross is viewed from Christ’s perspective rather than the viewer’s. From this perspective:

- The upward slant aligns with Jesus’ right side, where Dismas was, symbolizing salvation.

- The downward slant aligns with Jesus’ left side, where Gestas was, symbolizing rejection.

This idea of a reversed perspective aligns with how religious language often functions—it reconfigures perception to emphasize theological meanings. In fact, religions themselves can be understood as “backward languages“—systems of meaning that invert conventional structures to reinforce specific narratives.

Beyond its theological symbolism, the three beams are also popularly associated with the Trinity—Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. This connection gains further significance when considering the three dimensions of language. If the Orthodox Cross is understood as a linguistic metaphor, the slanted beam could symbolize the manipulation of language itself, reflecting how religious narratives are shaped and structured. From this viewpoint, the reversed perspective of the symbol would make sense, reinforcing the idea that religious language operates in a way that alters perception.

Additionally, the slanted beam may also reflect the way Jesus’ feet were positioned during the crucifixion. In some historical depictions, Jesus’ feet were nailed separately, with one foot placed on each side of the slanted beam. Alternatively, a slanted or slightly angled support beam may have been used to increase suffering, as it would force the crucified person to push up for air, leading to eventual exhaustion. Some traditions suggest that Christ’s body leaned slightly to one side, which could also explain the slant.

The design of the Orthodox Cross is common in Eastern Orthodox Christianity, particularly in Slavic traditions, and is often found in churches, icons, and religious art. It serves as both a historical reminder of the crucifixion and a representation of complex theological and linguistic themes within Orthodox belief.

The Chi Rho is an ancient Christian symbol that was widely used in the Roman Empire, particularly after Emperor Constantine adopted it in the early 4th century. It became one of the most recognizable symbols of Christianity, appearing on coins, military standards, and church decorations. The symbol itself consists of two overlapping Greek letters: Chi (Χ) and Rho (Ρ), which are the first two letters of Χριστός (Christos), the Greek word for “Christ” or “Anointed One.”

At first glance, the Chi Rho looks like the letter P intersecting with the letter X, leading many to refer to it as “XP.” However, the design is more than just a monogram—it is actually a depiction of Jesus on the Cross. The letter P represents Jesus himself, while the letter X symbolizes the cross. Crucifixion crosses came in various shapes, including the T-shaped crux commissa, the †-shaped crux immissa, and the X-shaped crux decussata, also known as St. Andrew’s Cross.

Another interpretation suggests that the P in Chi Rho isn’t actually a P but rather the letter R. This idea is reinforced by the theory of the suppedaneum, the footrest on Jesus’ cross, which was often depicted as tilted. In this view, the two legs of the letter R symbolize Jesus’ legs, with the additional stroke merging into the letter X. This would make the Chi Rho not just a reference to Christ’s title but a symbolic representation of His crucifixion itself. Hence why He’s called Xristos.

The Trefoil Cross is a symbol that combines the traditional Latin Cross shape with three rounded lobes at the end of each arm, creating a design that resembles a trefoil, or three-leaf clover. This shape is often associated with the Trinity in Christian symbolism, representing the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. Unlike a standard Latin Cross with straight or pointed ends, the trefoil design gives it a softer, more organic look, which has made it popular in both religious art and heraldry. It can be found in churches, stained glass windows, and even coats of arms, often serving as a decorative yet symbolic emblem.

The Jerusalem Cross is a distinctive symbol featuring a large central cross with four smaller crosses in each quadrant. It was associated with the Kingdom of Jerusalem, which was established by Crusaders in the 12th century, and has since become a widely recognized emblem of Christianity. The design is often interpreted as representing the five wounds of Christ or the spread of Christianity to the four corners of the world. Because of its strong connection to the Crusades, it is also commonly referred to as the Crusader Cross. While the term Crusader Cross can sometimes refer more broadly to different crosses used during the Crusades, the Jerusalem Cross is the one most commonly associated with the name. Traditionally, it is depicted in red, making it a striking and easily recognizable symbol that has appeared in church decorations, coats of arms, and religious jewelry throughout history.

The Pattée Cross is a symbol most associated with the violent enforcement of Christianity during the Crusades. This cross features broad arms that narrow toward the center, creating a bold and militaristic design. It was widely used by the Knights Templar, one of the most infamous Christian military orders, as well as other Crusader groups like the Knights Hospitaller and the Teutonic Order. These knightly orders played a major role in the Crusades, using extreme brutality to expand Christian rule and suppress non-Christian populations. The Templar knights, in particular, wore a simple red Pattée Cross on their white tunics, signifying their willingness to fight and die in their religious wars. Their campaigns, driven by a belief in divine justification for conquest, led to massacres, forced conversions, and widespread destruction. The red color of their cross further reinforced its connection to bloodshed, both their own and that of those they deemed enemies of the faith. While originally a battlefield emblem, the Pattée Cross has continued to appear in various forms, sometimes romanticized but always carrying the legacy of its violent past.

The Christian Cross has long been associated with sacrifice and redemption, but its symbolism extends beyond these interpretations. One striking connection is its resemblance to a sword. A cross consists of a vertical and horizontal line intersecting at a central point, just as a sword has a blade extending upward and a crossguard near its base. The Knights Templar, known for their military campaigns, reinforced this symbolism by prominently displaying the Pattée Cross on their shields—merging the ideas of sword and shield. This conveys the message that what is presented as a defense is often used as an attack.

Jesus Himself alluded to this martial symbolism when He declared in the Bible, “I have not come to bring peace, but a sword” (Matthew 10:34). This statement highlights the Christian belief that peace can only be achieved through violence—an idea reflected throughout history in religious wars, crusades, and forced conversions. The cross, as a symbol of faith, is also a symbol of conquest.

Another layer of this symbolism can be found in the connection between Jesus and the sun. The letter S, notably, is often associated with the sun. This brings an intriguing observation: the words “sword” and “words” are anagrams of each other, with the only difference being the placement of the letter “S.” If the S is moved from the end of “words” to the beginning, it spells “sword“—a movement from east to west, mirroring the apparent motion of the sun across the sky.

This reveals a hidden truth about the language we’ve been taught. Words of fictional concepts function as weapons. They manipulate, deceive, and cause conflict, much like the sword. This corruption of language is reflected in the way power structures have historically used words to control, mislead, and justify violence. The Christian Cross, when understood as a sword, exposes this dual nature—what is claimed to be salvation is a tool of division and conquest.

The Christian cross is a phallic symbol. Its shape alone makes this obvious—an upright vertical form has always been associated with masculinity, fertility, and generative power across countless cultures. This isn’t just coincidence; it follows a long-standing pattern where anything tall and erect, from obelisks to pillars, represents the male force, while the horizontal (phallus) also symbolizes masculinity—both in contrast to hollow forms, which symbolize the feminine.

Long before Christianity, civilizations were already using phallic symbols in religious and spiritual contexts. The Egyptian Djed pillar, linked to Osiris, embodied stability and resurrection—both closely tied to fertility myths. The Hindu lingam, a direct representation of Shiva’s creative force, serves the same function. Christianity did not emerge in a vacuum. It inherited and absorbed symbols from the surrounding cultures, and the cross is no exception.

Beyond just its shape, the deeper themes of the cross reinforce its phallic nature. The crucifixion itself is filled with symbolism of suffering, sacrifice, and transformation—ideas connected to ancient fertility rites and the cycle of death and rebirth. The act of Christ’s body being affixed to the cross can be seen as a merging of physical and spiritual forces, much like how phallic symbols in other traditions represent the bridge between earthly life and divine power.

Christian mysticism also reinforces this. The cross has often been associated with the divine masculine, mirroring the way Mary embodies the divine feminine. It represents fatherhood, authority, and creation. In esoteric traditions, the cross is even more explicit in its sexual symbolism. The line is the phallus, and the hollow form represents the receptive principle—the womb or the earth. This is a direct expression of the union of opposites, a concept central to alchemy and other mystical traditions.

Despite modern Christianity avoiding this discussion, the fact remains: the cross is a phallic symbol. Its form, its historical lineage, and its deeper symbolic meaning all confirm it. Whether consciously acknowledged or not, it stands in a long tradition of sacred symbols representing masculinity.

The Christian Cross, when unfolded, becomes a cube—a rigid and enclosed form. The transformation is not a disappearance but a shift in presentation. While the cross is often associated with sacrifice and endurance, its geometric root reveals a structured system: a box by another name. The cube itself symbolizes a prison of fantasy. This symbolism is not limited to Christianity. The cube stands at the center of the Kaaba, the holiest site in Islam, around which millions move in devotion. In the Star of David, the emblem of Judaism, a cube can be traced at the center of its interlocking triangles. These aren’t isolated symbols—they point to how the three major Abrahamic religions are intertwined, forming parallel dimensions of the same language. All carry the same concealed message: confinement dressed as faith. The structure remains the same; only the form shifts. Whether it’s the cross, the Kaaba, or the hexagram, the underlying geometry speaks of boundaries—prisons of fantasy that guide belief without visible walls, maintaining control through illusion.

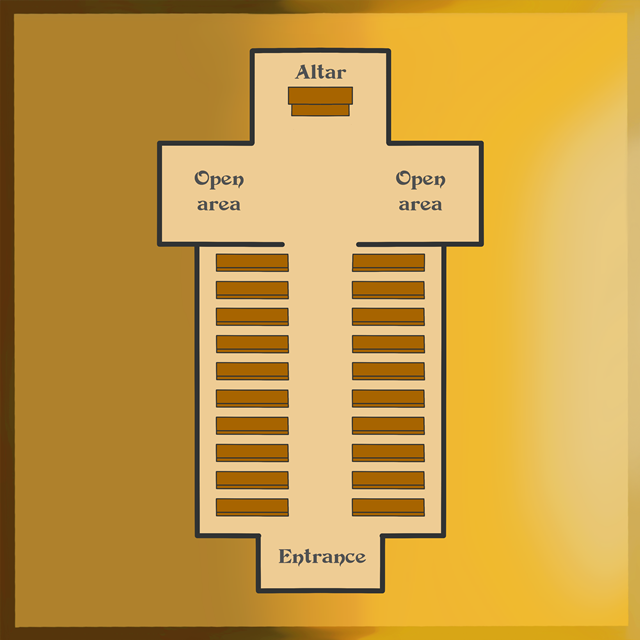

The interior layout of a church is often designed to represent the Christian Cross. The lower part of the cross corresponds to the entrance of the church. This is usually where the rows of pews are located, with seating on both sides of the central aisle. In front of the front pews, there are typically open areas on each side without seating. At the very front of the church is the altar, which represents the top of the Christian Cross.

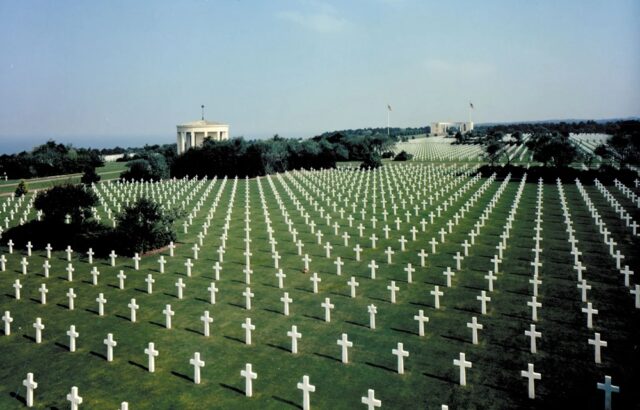

The Christian Cross is frequently used as a memorial marker, symbolizing remembrance, sacrifice, and faith.

It often appears in the form of a wooden grave cross or a carved stone cross placed at burial sites. In cemeteries around the world, and especially in the context of military history, rows of wooden grave crosses are commonly seen—particularly in mass military burials.

These markers, while intended to honor the dead, also carry a haunting visual weight. In such settings, the repetition of the symbol emphasizes the scale of loss. For some observers that are nonbelievers, it highlights how religion—especially when intertwined with nationalism or warfare—can influence people on a massive scale, leading them to kill or die for ideas that are fictional.

Thus, the use of the cross as a memorial marker does more than commemorate the dead; it invites reflection on the deeper forces that shape human conflict, loyalty, and meaning.

The following example is an image from The Normandy American Cemetery and Memorial honouring U.S. soldiers who died on European soil in World War II, Colleville-sur-Mer, France.

The cross has appeared and appears on many national flags, often as a central or dominant feature. Flags are designed to convey the identity and foundational principles of a nation, and their symbols often reflect the core ideology or language in which a nation’s people are conditioned to think. In the case of nations that bear the cross, this symbol represents more than just historical or religious heritage—it signals that these nations operate within the framework of Christianity as a guiding influence.

While some argue that the cross on flags is a mere nod to tradition, its presence serves as a persistent reinforcement of Christian ideology in national identity. Whether through cultural institutions, legal structures, or historical narratives, the cross on these flags subtly affirms that Christianity remains a fundamental lens through which these societies interpret morality, law, and governance. Even in nations that claim to uphold secular principles, the embedded presence of the cross on their flags suggests an underlying assumption that Christianity forms the foundation of their national consciousness.

The following gallery showcases national flags featuring a cross in some form, though it does not include every flag on which a cross has appeared or currently appears. While some of these flags incorporate a Christian symbol, the nations they represent may not officially identify as Christian. Nonetheless, Christianity is often deeply embedded in their language, culture, and values, even if it is not the sole influence reflected in the flag’s design. The names of these flags are:

- Alternate Flag of Portugal.

- Flag of Angola.

- Flag of Australia.

- Flag of Bangsamoro.

- Flag of Bermuda.

- Flag of Brazil.

- Flag of Burundi.

- Flag of Christmas Island.

- Flag of Denmark.

- Flag of Dominica.

- Flag of England.

- Flag of Fiji.

- Flag of Finland.

- Flag of Georgia.

- Flag of Great Britain.

- Flag of Greece.

- Flag of Guernsey.

- Flag of Iceland.

- Flag of Jamaica.

- Flag of Jersey.

- Flag of Malta.

- Flag of Moldova.

- Flag of Montenegro.

- Flag of Montserrat.

- Flag of New Zealand.

- Flag of North Macedonia.

- Flag of Northern Ireland.

- Flag of Norway.

- Flag of Oman.

- Flag of Papua New Guinea.

- Flag of Samoa.

- Flag of San Marino.

- Flag of Saudi Arabia.

- Flag of Scania.

- Flag of Scotland.

- Flag of Serbia.

- Flag of Seychelles.

- Flag of Slovakia.

- Flag of Spain.

- Flag of Sri Lanka.

- Flag of Sweden.

- Flag of Switzerland.

- Flag of the Basque Country.

- Flag of the Dominican Republic.

- Flag of the Faroe Islands.

- Flag of the Marshall Islands.

- Flag of the United Kingdom.

- Flag of Tokelau.

- Flag of Tonga.

- Flag of Vatican City.

- Flag of Åland.

Many people claim they are not indoctrinating their children into Christianity, insisting that children should be free to choose their own beliefs when they’re older. However, actions often speak louder than intentions. For example, during national holidays or celebrations, it’s common for children to be handed flags that prominently display the Christian cross—sometimes by parents, sometimes by public institutions like schools. Children are then encouraged to wave these flags with pride, often without any understanding of the symbol’s religious meaning.

This practice blurs the line between national identity and religious symbolism. When a Christian symbol like the cross is embedded into national celebrations and treated as a neutral or unproblematic tradition, it subtly teaches children to associate Christianity with patriotism, unity, and pride. This is especially impactful when it happens in public schools, which are supposed to remain neutral in matters of religion.

Whether intentional or not, this normalization of a religious symbol in a national context contributes to indoctrination. It sends a quiet but powerful message: “This is who we are.” And for children, who are still forming their worldview, that message can be deeply formative—often before they even realize they’re being influenced.

Articles:

Celtic Cross

Definition: The “Celtic Cross” is a form of Christian Cross featuring a traditional cross with a nimbus or ring surrounding the intersection. It is distinct for its combination of a…

Chi Rho

Definition: “Chi Rho” is one of the earliest forms of christogram, formed by superimposing the first two Greek letters of the word “ΧΡΙΣΤΟΣ” (Christos)—chi (Χ) and rho (Ρ). It serves…

Crucifix

Definition: A “crucifix” is a cross that bears the representation of Jesus Christ’s body, known as the corpus. Etymology: The word “crucifix” comes from the Latin “crucifixus,” meaning “one fixed…

Eye of Jesus

Definition: The term “Eye of Jesus,” also known as the “Eye on the Cross,” typically refers to a metaphorical or symbolic concept within Christian theology and spirituality. It is not…

Greek Cross

Definition: The “Greek Cross” is a type of cross with four arms of equal length, intersecting at right angles. Etymology: The term “Greek Cross” originates from its prominent use in…

Jerusalem Cross

Definition: The “Jerusalem Cross,” also known as the “Crusader’s Cross,” is a Christian symbol consisting of a large cross potent (a cross with crossbars at the ends) surrounded by four…

Maypole

Definition: A “maypole” is a tall wooden pole, often decorated with ribbons, flowers, and other ornaments, or made to resemble the Christian Cross, that serves as the focal point for…

Orthodox Cross

Definition: The “Orthodox Cross,” often referred to as the Russian Orthodox Cross, is a distinct Christian Cross associated particularly with the Eastern Orthodox Church. Etymology: The term “Orthodox” comes from…

Papal Ferula

Definition: A “papal ferula” is a ceremonial staff carried by the Pope. Etymology: The term “ferula” comes from the Latin word “ferula,” meaning “rod” or “staff.” It has historically been…

Patriarchal Cross

Definition: The “Patriarchal Cross” is a variant of the Christian Cross featuring two horizontal crossbars, with the upper one shorter than the lower one. Etymology: The term “patriarchal” comes from…

Pattée Cross

Definition: The “Pattée Cross” (also spelled “Pattee”, “Patee”, or “Paty”) is a distinct form of Christian Cross with arms that are narrow at the center and flare out in a…

Southern Cross

Definition: The “Southern Cross” refers to a prominent constellation officially known as “Crux.” It is visible in the southern hemisphere and is composed of five stars that form a cross-like…

Sword

Definition: A “sword” is a bladed weapon used primarily for cutting or thrusting. Typically, it consists of a long metal blade attached to a hilt with a guard. Etymology: The…

Tau Cross

Definition: The “Tau Cross” is a T-shaped cross, resembling the Greek letter tau (Τ or τ). Etymology: The term “Tau” derives from the Greek letter “ταῦ” (tau), which was used…

Trefoil Cross

Definition: The Trefoil Cross is a symbol that combines the traditional Latin Cross shape with three rounded lobes at the end of each arm, creating a design that resembles a…

White Nationalist Celtic Cross

Definition: The term “White Nationalist Celtic Cross” refers to a specific adaptation of the traditional Celtic Cross that has been appropriated by white nationalist and white supremacist groups. Etymology: The…

Religion:

The Bible makes numerous references to the cross:

In the Bible, in Matthew 16:24, it says: “Then Jesus said to His disciples, ‘Whoever wants to be my disciple must deny themselves and take up their cross and follow me.’”

In the Bible, in 1 Corinthians 1:18, it says: “For the message of the cross is foolishness to those who are perishing, but to us who are being saved it is the power of God.”

In the Bible, in Galatians 6:14, it says: “May I never boast except in the cross of our Lord Jesus Christ, through which the world has been crucified to me, and I to the world.”

In Islam, Jesus (Isa) is respected as a prophet, but the crucifixion is denied in the Quran.

In the Quran, in Surah 4:157, it says: “And [for] their saying, ‘Indeed, we have killed the Messiah, Jesus, the son of Mary, the messenger of Allah.’ And they did not kill him, nor did they crucify him; but [another] was made to resemble him to them.”